The Mons Huygens Myth

Download a paper on this topic (DOI: 10.31219/osf.io/agpr4)

Mons Huygens is the tallest mountain on the Moon, it is just over half the height of Mount Everest

From here on let's call this factoid "The Tall Tale". A quick search shows how widely it's spread. And it's still popping up in new content. When I checked the first few pages of search results, I found it getting told in the following places, though I'm sure you can find more:• Social media responses

• Blog posts

• Amateur astronomy club newsletters

• Image hosting websites (like astrobin)

• Infomercials by telescope manufacturers

• Articles by popular astronomy personalities

• Books

• Magazines

• Catalogs of the Moon's features

• Space news websites

• Local government websites

• Promotional material from planetariums

• Releases from space agenciesNow, there’s some pretty authoritative sources in that lot. The Tall Tale even extends into educational resources, including community college course materials, teachers' guides, student study aids, and children's quizzes. It's hard to get any more embedded than that.BUT. When the Tall Tale gives a height for Mons Huygens, it's not always the same height. Or even close to the same height. In fact, heights are all over the place. You come across 4600m, 4700m, 5000m, 5400m, 5500m, 6.1 km, 16000 feet, 18000 feet, 18046 feet, 3 miles, and 3.3 miles. That's some spread for ‘the tallest mountain on the Moon’! Which then makes you wonder how true The Tall Tale is. (Spoiler: Not Very). Let's dig in and find out...

Profiling Mount Everest

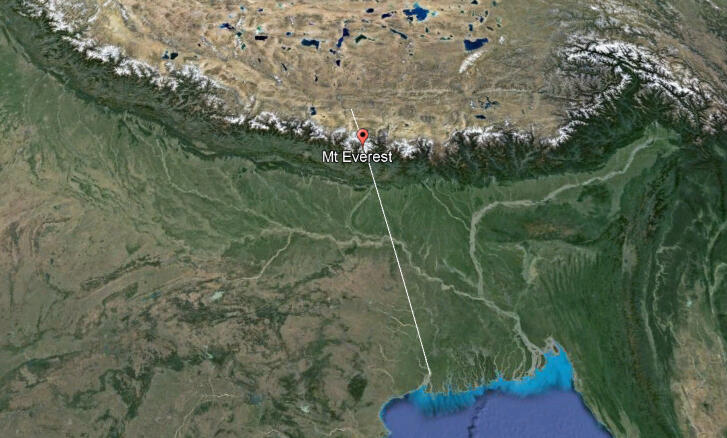

The first thing we need to do is get a handle on what Mons Huygens is being compared to: Mount Everest. If Mons Huygens' 4700m (say) is meant to be ‘just over half the height of Mount Everest’, the comparison’s being made with the height of Everest's summit above sea level, which is 8848m. But as Fig 1 shows, the nearest sea is 700 km away from Everest's peak, at the Bay of Bengal.

Fig 1 - Sea to summit of Mount Everest (Google Earth Pro)

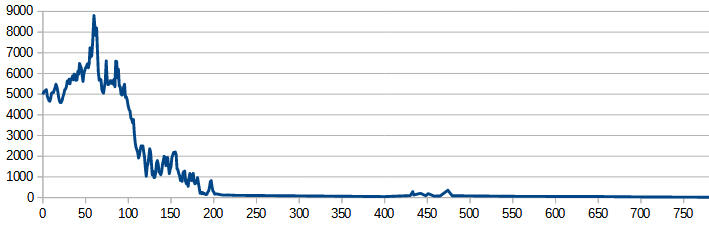

Fig 2 - Height profile from sea to summit of Mount Everest (Google Earth Pro)

Fig 2 shows what the height profile looks like along the transect in Fig 1. What this picture says is that if you intend to Climb Everest, you should really begin your trek with salt water dripping off your toes from the extreme right of Fig 2. It's only a partial climb if you start from Kathmandu at an elevation of 1400m, or Lukla 2860m up. As for getting dropped off at Everest base camp and summitting from there, you're only scaling the peak that juts up from the Tibetan plateau in that case.But it’s also pretty clear from Fig 2 that there’s very little change in elevation over most of the distance from sea to summit. So to make things easier, let’s just consider the base of the Everest mass to be where the terrain begins to rise significantly, which in Fig 2 looks to be at around the 200 km mark. Now let’s compare this business end of the height profile with 'the tallest mountain on the Moon’.

Mount Everest vs Mons Huygens

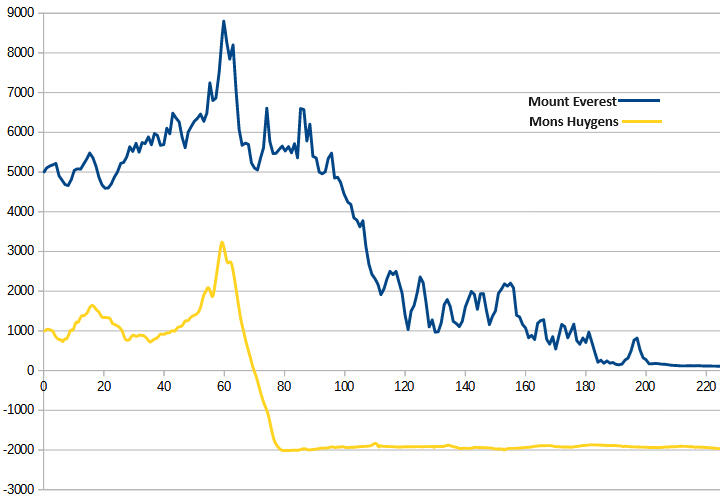

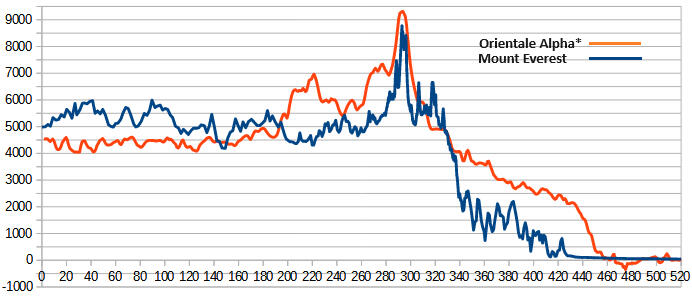

Fig 3 - Height profiles of Mount Everest, Mons Huygens (Google Earth Pro, LROC Quickmap)

Fig 3 shows Mons Huygens' height profile against our horizontally truncated Everest profile. Notice that Mons Huygens' base isn’t on the lunar datum - the Moon’s equivalent of sea level. The base is 2000m below it on Mare Imbrium – the flat-surfaced lava fill in the Imbrium basin. Before the lava flooding in the Moon’s distant past, the mountain’s base would definitely have been lower than this, approaching the original basin’s depth, and so Mons Huygens would have been taller. Anyway, next let's shift Mon Huygens' profile up by 2000m so that its base is at the same elevation as Everest's. It just helps with the comparison.

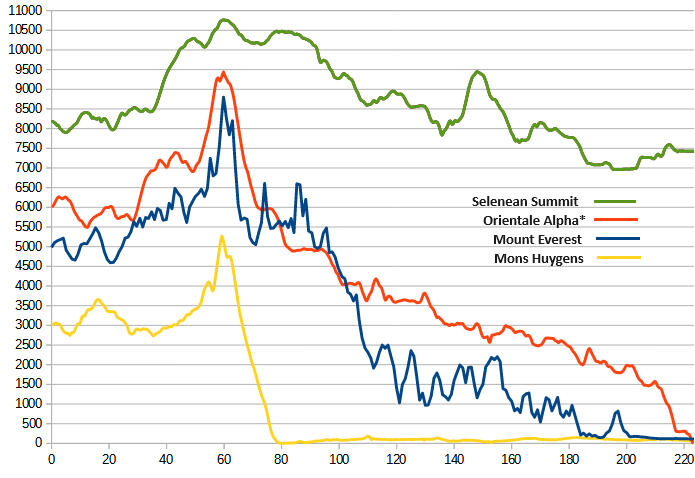

Fig 4 - Height profiles of Orientale Alpha*, Mount Everest, Mons Huygens (Google Earth Pro, LROC Quickmap)

Right, from Fig 4 we can now just read off Mons Huygens’ base-to-peak height – it’s 5300m tall.As Fig 3 shows, if Mons Huygens were on Earth, it would only rise 3300m out of the sea. This suggests Mons Huygens isn’t really the right Moon mountain to be comparing with Everest. For a closer match, we should start with terrain that's already as elevated as possible from the lunar datum, not kilometres below it. That excludes the mountains around the Imbrium basin, including Mons Huygens. The lunar farside highlands however, is such terrain.So let's first examine the highest point on the Moon's farside highlands, and the Moon itself: Selenean Summit. At 10785m above datum, Fig 4 (green) shows its profile. In a sense, Selenean Summit is the Moon's 'Everest' due to its elevation, but Everest is a mountain and Selenean Summit really isn't; it's more of a plateau with a slope of between 3° and 5° from the surrounding terrain to the summit, making it unlikely to be ever designated a 'Mons'.But the next highest location in the farside highlands is a mountain. This peak, which I've just called Orientale Alpha, is on the outer south-west rim of the Orientale basin, and its elevation profile is in orange in Figure 4.

A Lunar Everest

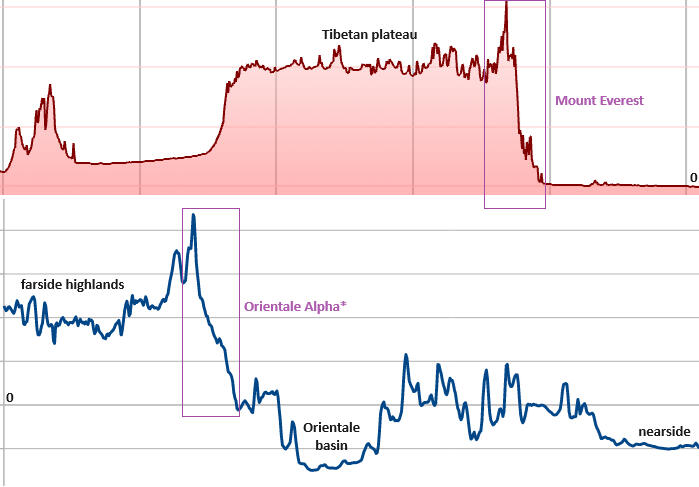

It's clear from Fig 4 that from 6000m to its summit at 9460m, Orientale Alpha rises with a similar slope to Mons Huygens. And overall Orientale Alpha's elevation profile looks uncannily like Everest's, only pushed up and smoothed out a bit more. So this truly is the Moon's Everest!Figure 5 offers a more zoomed-out view of the two mountains, and they maintain their similarity at this scale. Both the lunar farside highlands and the Tibetan plateau are at comparable elevations, with the respective peaks situated on their edge, and there's also some correspondence in the slope of the terrain down to near-datum from there.The even wider terrain profile in the bottom panel of Figure 6 highlights that the Orientale basin is situated at the transition between the thinner nearside crust and the thicker farside crust.

Fig 5: Medium zoom terrain profiles of Mount Everest, Orientale Alpha (Google Earth Pro, LROC Quickmap)

Fig 6 - Widefield terrain profiles of Mount Everest, Orientale Alpha* (Google Earth Pro, LROC Quickmap)

So we now have what we need to replace The Tall Tale. We go from this:

Mons Huygens is the tallest mountain on the Moon, it is just over half the height of Mount Everest

To:1) Selenean Summit is the highest point on the Moon, it is 1937m higher than Mount Everest

2) An unnamed mountain near the Orientale basin on the lunar farside is the highest mountain on the Moon, it is 612m higher than Mount Everest

3) Mons Huygens is 5300 meters tall, about 60% of the height of Mount EverestUpshot: on the one hand The Tall Tale understates Mons Huygens’ base-to-peak height, which is a tad more than ‘just over’ half the elevation of Mount Everest's summit. On the other, much bigger hand, the Moon’s highest mountain actually exceeds Everest’s height.The ill-fated Astrobotic Peregrine Mission 1 in early 2024 included a piece of Mount Everest's summit in its eclectic payload. The lander was destined for the Gruithuisen domes on the Moon, which are thought to be formed of a very viscous type of lava that's unusual for the Moon, making this region a prime target for exploration. At under 2 km base-to-peak, these domes are likely the tallest volcanic structures on the Moon, but that's not saying much as unlike Mars, the Moon's not known for its immense volcanoes. So it'd be wonderfully poetic to one day send a piece of Everest to its lunar doppelganger, Orientale Alpha. As a bonus, the Orientale basin happens to be the Moon's youngest and best-preserved multiring impact basin, and so offers a great opportunity to advance our knowledge of lunar geology. Its sparse mare basalt coverage exposes the original basin floor and a well-preserved impact melt sheet. Analysis of the basin's rings would provide insights into the lunar interior's structure and composition, while its pyroclastic deposits might reveal details about the lunar water cycle.

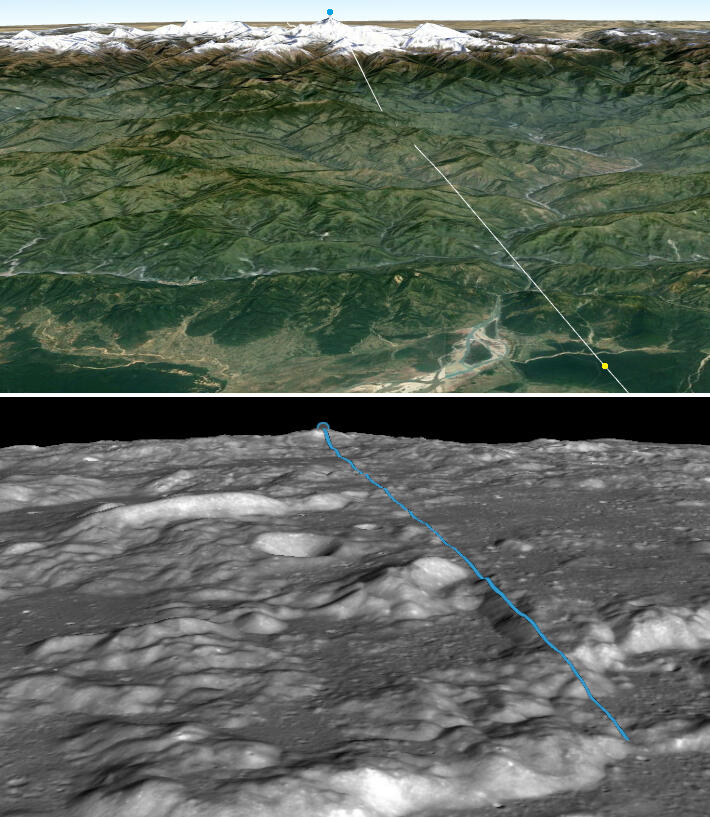

Fig 7 - 3D terrain views. Top: Mount Everest (Google Earth Pro). Bottom: Orientale Alpha* (LROC Quickmap)

Fig 7 shows what Everest and Orientale Alpha physically look like, along the height profiles of Fig 4.In the top panel of Fig 7, we're looking east-west along the Himalayas. Everest's summit is highlighted by a blue dot. The white line traces out the blue height profile in Figure 4. The terrain starts rising significantly from the yellow dot, which is in the same location as the far right of the height profile.The bottom panel of Figure 7 shows the view towards Orientale Alpha’s summit. The blue line traces out the orange height profile in Figure 4, beginning at 0 datum and reaching up to 9460m.The top panel gives us familiar visual cues to help with perspective and scale—things like the forested plain where the terrain starts to rise, winding rivers, hills that step up to larger mountain folds, snow-capped peaks, and a plateau in the background. In stark contrast, the lunar landscape in the bottom panel feels completely alien. It’s all monochrome, with little variation in texture and no familiar landmarks to help gauge size and distance. For example, the crater above the center is 15 km wide, and the ridge to its upper left is 2500m high. It’s hard to even sense the upward slope from the bottom to top of image.If Orientale Alpha were in Everest’s place on Earth, it could potentially be less technically demanding to climb thanks to its gentler slopes and the lack of vertical faces, but the few extra hundred meters into the ‘death zone’ would make it considerably more difficult to summit.

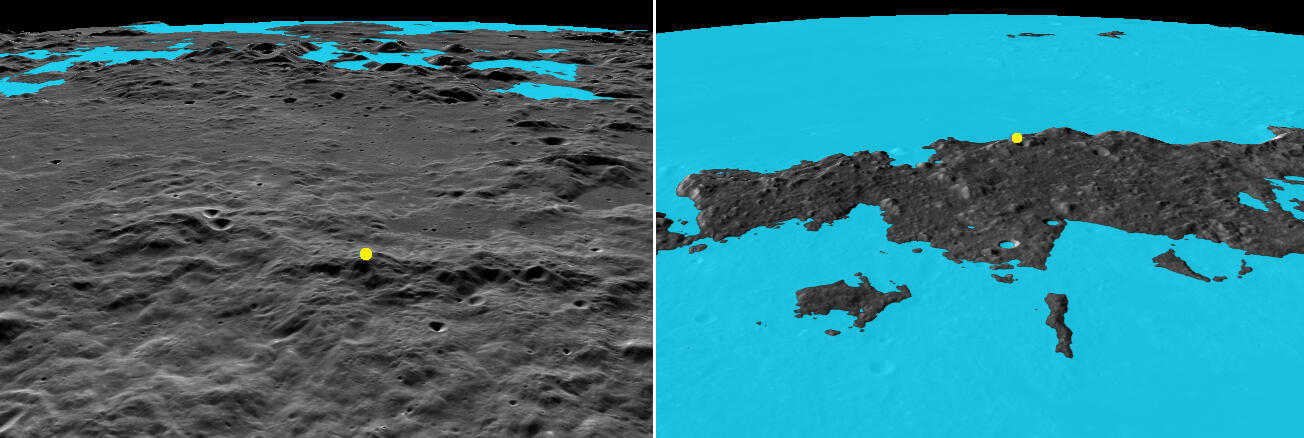

Fig 8 - 3D terrain views. Left: Orientale Alpha*. Right: Mons Huygens (both LROC Quickmap)

Fig 8 contrasts the environments of Orientale Alpha and Mons Huygens. Their peaks are marked by yellow dots. Here simulated water fills everything up to 0 datum, like Earth's seas. In Orientale Alpha's case, we're looking in the opposite direction to Fig 6 - from the peak back towards the Orientale 'sea', with the vast nearside 'ocean' stretching beyond. It's a 9460m drop from the peak to any point on the 'water's edge'. In the nearside 'ocean', landmasses are mere islands, like the Apennine range in the right panel that hosts Mons Huygens. Here nearly 40% of Mons Huygens' height is submerged.

Falling Short

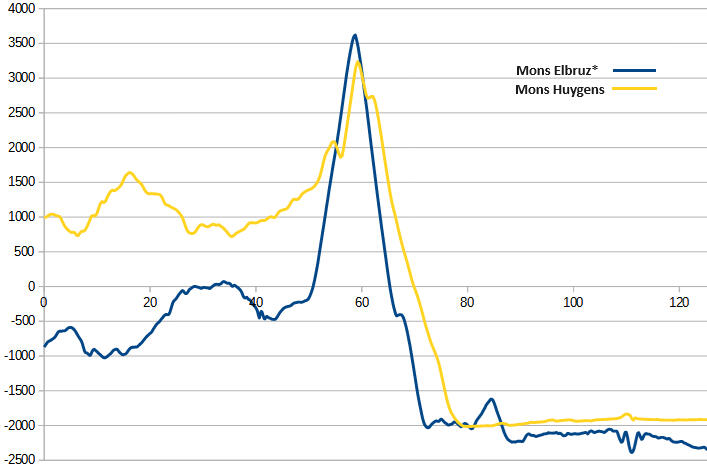

Everest-topping Orientale Alpha aside, Mons Huygens hasn’t deserved its crown for years. It isn't even the tallest peak in the Imbrium basin’s rings! That happens to be an unnamed ridge on the rim of the half-submerged crater Calippus C, in the Caucasus mountains. Through a telescope, you can see it casting an impressive shadow when the terminator is close, as captured in the image of Fig 9 right panel. Profiling this ridge with LROC Quickmap reveals it's more than 300m taller than Mons Huygens.One proposed name for it is Mons Elbruz, which I think is fitting since Mount Elbrus is the highest peak in the Earth's Caucasus range (after which the lunar range is named), and it has the same elevation as Mons Elbruz’ base-to-peak height: 5640m. Fig 10 shows Mons Elburz’ height profile against Mons Huygens’.

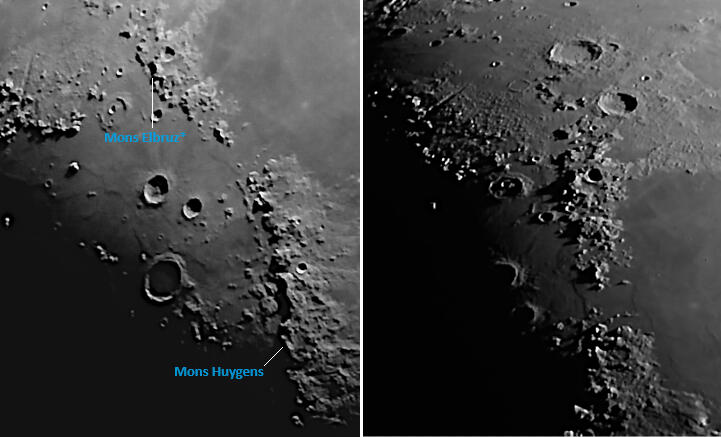

Fig 9 - The Apennine and Caucasus Mountains - telescopic images (8" untracked Dobsonian)

Fig 10 - height profiles of Mons Elbruz*, Mons Huygens (LROC Quickmap)

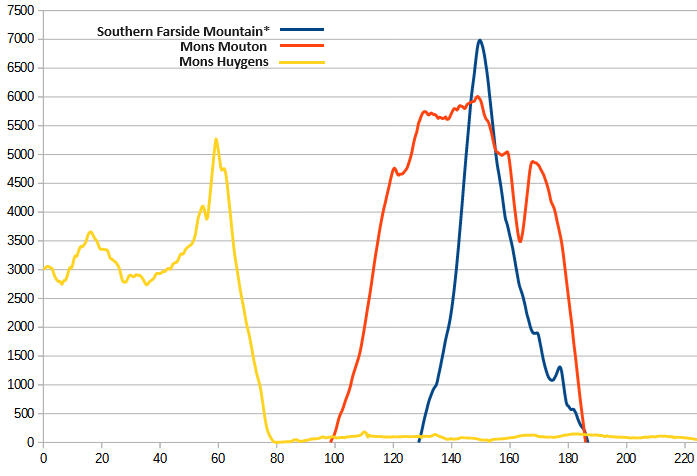

In early 2023, the IAU officially named a 6000m free-standing mountain in the lunar south polar region Mons Mouton, after NASA mathematician and computer programmer Melba Roy Mouton. It was previously informally referred to as Leibnitz Beta.The Moon’s tallest free-standing mountain is 7000m base-to-peak, which makes it almost 2000m taller than Mount Kilimanjaro, Earth’s tallest free-standing mountain. Or 1300m taller than Mons Huygens. Or 80% the height of Mount Everest. Amazingly, it too is unnamed. Some simply refer to it as Southern Farside Mountain.Unlike Mons Mouton, which is a table-topped, mesa-like structure, Southern Farside Mountain has a classic, triangular shape - the kind of thing you might have drawn as a kid to depict a mountain. However both mountains are likely part of what remains of the rim of one of the largest craters in the Solar System – the South Pole-Aitken basin. Fig 11 shows how they measure up against Mons Huygens, with the bases of all three aligned to 0 datum for ease of comparison.

Fig 11 - height profiles of Southern Farside Mountain*, Mons Mouton, Mons Huygens (LROC Quickmap)

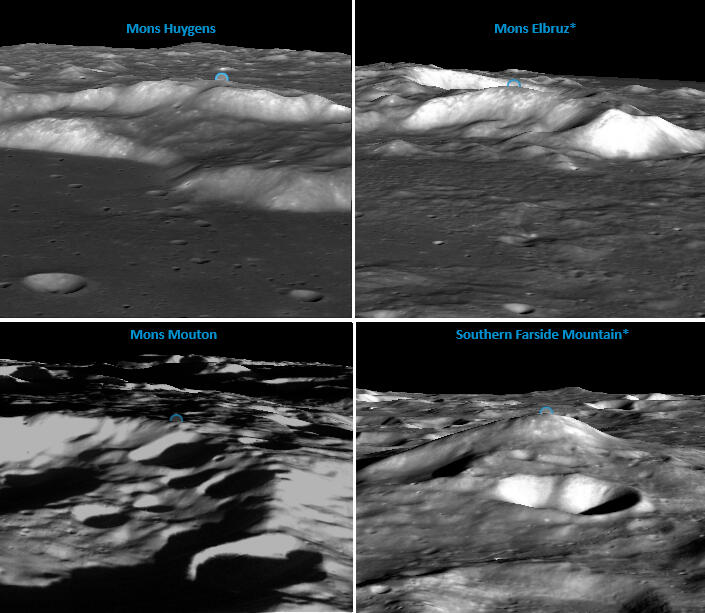

Figure 12 presents oblique 3D views of Mons Huygens together with the other three mountains discussed in this section that surpass it in base-to-peak height. Since Mons Huygens and Mons Elbruz both belong to ranges bordering Mare Imbrium, they have comparable base elevations, though the terrain in front of Mons Elbruz is more rubbly. The long shadows near the south pole and the flat top of Mons Mouton make that mountain somewhat difficult to discern clearly. No such issue though with volcano-esque Southern Farside Mountain.For more details about these mountains (their exact location, summit co-ordinates etc), please check out the companion site The Moon's Highs and Lows.

Fig 12 - 3D terrain views of Mons Huygens and three taller Moon mountains (LROC Quickmap)

Wrong For So Long

There’s probably a few reasons why The Tall Tale emerged, and why it keeps getting retold:Viewing Bias

The Apennine Mountains, which include Mons Huygens, are the most spectacular mountain range on the lunar nearside, no question. And they're centrally located for easy observation, so have been a magnet for astronomers and enthusiasts for generations. This sustained attention has made the peaks in this range some of the best known lunar features. So the notion that Mons Huygens is the tallest mountain on the Moon might partly stem from a kind of hero worship. When we deeply admire something or someone, we tend to attribute exaggerated qualities or abilities to them, beyond reality. In contrast, the Caucasus Mountains north of the Apennines are more modest looking, and simply haven't captured the collective imagination in the same way as the Apennines, despite hosting a taller mountain than Mons Huygens. Fig 9 left panel is a typical view of the two ranges from Earth.Also visibility of nearside features from Earth has led to a disproportionate emphasis on them. The tallest lunar mountains are all on the farside. But the principle of 'out of sight, out of mind' applies. Mons Huygens was heralded as the entire Moon's tallest long before enough was even known about the farside, and that reputation has persisted since. This bias also extends to difficult-to-see locations on the nearside. Mons Mouton's position in the south polar region means it's viewable obliquely from Earth only during times of favourable lunar libration, and despite its height, remains lesser known than Mons Huygens.Legacy Imprecision in Sizing Lunar Features

Even though the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has brought the Moon into sharper focus with unprecedented detail, its launch in 2009 is still pretty recent in the study of the Moon, and there's a lot of literature around with outdated estimates of Mons Huygens' height. As a result, it's easy to come across such material, which then influences new content.Informational Inertia

Once a piece of information becomes widely accepted, it gets an air of credibility, sometimes undeserved, making it hard to dislodge even when confronted with factual data.

Righting The Record

I think a concerted effort from multiple stakeholders is needed to ensure that only accurate information about lunar topography becomes widespread.Naming the Peaks

As this study shows, the most significant lunar mountains don't have official names from the IAU. This is a problem for clear communication and education. Without consistent names for them, myths like 'Mons Huygens is the tallest mountain on the Moon' are more likely to persist, and get taught.Educational Integrity

Wherever possible, educators should take opportunities to dig a little deeper to improve the quality of teaching materials. Tools like LROC Quickmap make it easier than ever to examine lunar features, and validate estimates.Boosting Citizen Science

Educators can inspire students by showcasing the possibilities of citizen science, and encouraging them to participate. There's an enormous amount of data available to the public, both in raw form and as engaging visual and interactive models. By fostering curiosity and allowing students to explore data themselves, teachers can spark new investigations and deepen understanding. This hands-on approach, which led to the findings presented here, makes science feel accessible to everyone, not just for 'lab-coat professionals'.Institutions Stepping Up

Although space agencies, planetary institutes, and universities that handle spacecraft data often have outreach programs, there's always room to go a step further in tackling common misconceptions. By identifying and correcting errors through media releases and articles, they can prevent these mistakes from spreading. It's like eradicating fire ants early, before even containment becomes an enormous challenge.Updating Primary Sources

Last but not least, hobbyists and enthusiasts, who often come across new findings in their fields of interest before the wider public, should feel empowered to update sources like Wikipedia. Many people rely on such sources for schoolwork, research and general knowledge, and their contributions can help ensure that this information remains accurate.

Closing Thoughts

We’re fascinated by the tallest mountains because they evoke a sense of awe and wonder. They resonate with us emotionally and spiritually. The highest peak has extra meaning – we see it as the ultimate challenge, a symbol of ambition and achievement.This is reflected online, where people imagine climbing the tallest mountains in the Solar System, mentioning Olympus Mons on Mars and Mons Huygens by name. And you can find Mons Huygens in the title of artworks. This has no doubt stemmed from the mistaken belief Mons Huygens is the Moon’s tallest mountain.Which is to say that since the most significant mountains matter, they ought to be properly identified.

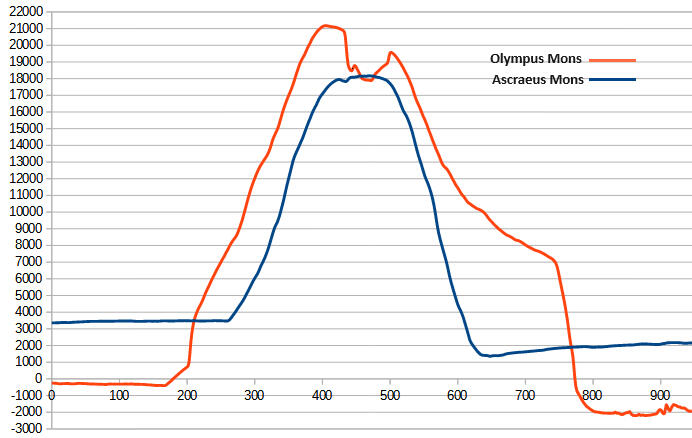

Fig 13 - height profiles of Olympus Mons, Ascraeus Mons (Mars Quickmap)

Can you imagine Mount Everest remaining unnamed? Or waking up one day to learn that a higher mountain than Everest had been discovered?Consider Olympus Mons, which has always been correctly cited as Mars' highest peak in elevation, and its tallest mountain base-to-peak, even though Mars, at its closest, is over 100 times further from us than the Moon. Figure 13 shows how Olympus Mons compares to Mars' second tallest mountain, Ascraeus Mons. Again, there's never been confusion over which is Mars' tallest; there's little chance someone will come across a Martian mountain taller than Olympus Mons, and as you'd expect all of Mars' tallest peaks are named.The Moon deserves the same consideration.

Created by: Jim Singh - Electrical Engineer, Amateur Astronomer, Science Writer. Last Updated: March 2025. If you've found this site useful or have feedback, please drop me a line at jimmyboysingh. Follow that name with an at, then gmail and finish up with a dot and a com.